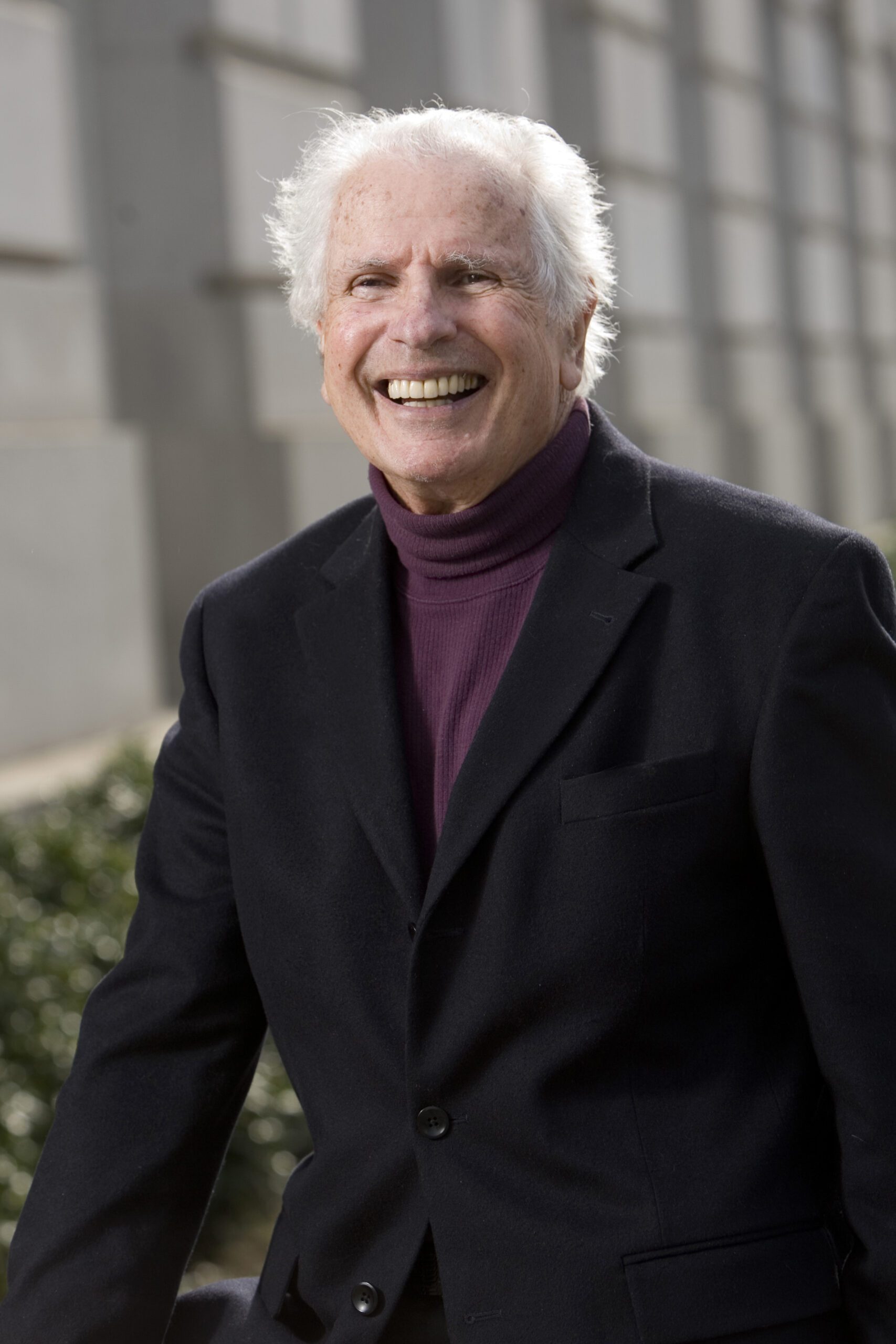

UC Law SF Celebrates Joseph Grodin’s Legacy on 90th Birthday

Colleagues and friends of former California Supreme Court Justice Joseph R. Grodin, who taught full time at UC Law SF from 1972 to 2005, recalled his legacy in celebration of his upcoming 90th birthday on Aug. 30.

They praised the thoughtful and gregarious scholar for leaving an indelible mark not only on his many students and colleagues at UC Law SF but also on the development of law and public policy. What many recall most vividly is that his intellect was always accessible.

They praised the thoughtful and gregarious scholar for leaving an indelible mark not only on his many students and colleagues at UC Law SF but also on the development of law and public policy. What many recall most vividly is that his intellect was always accessible.

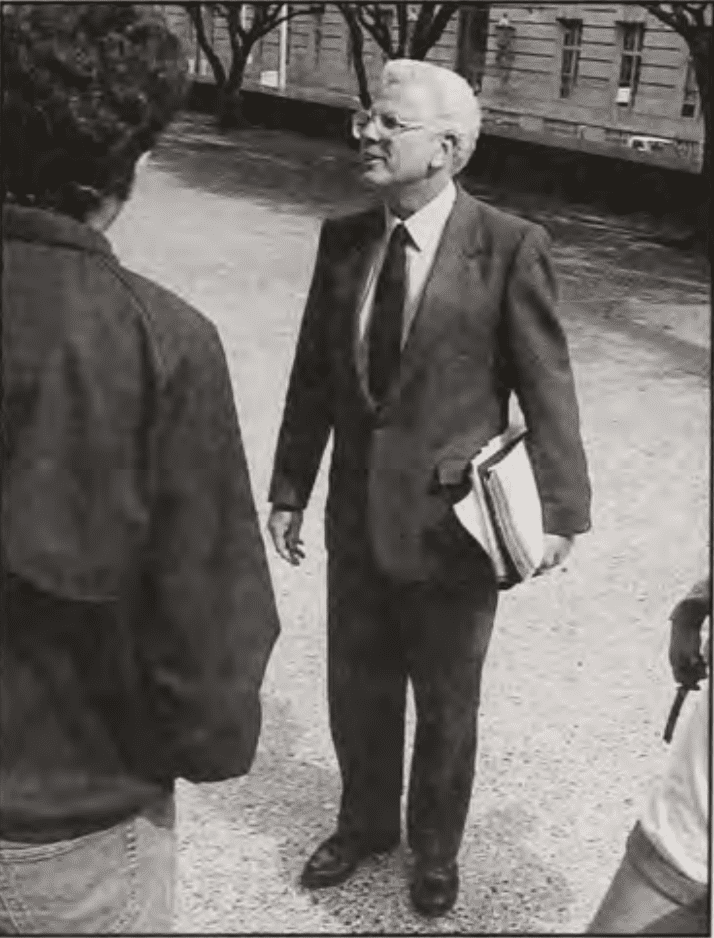

As a new UC Law SF professor in the early 1970s, Grodin would frequently drop by the UC Law SF Journal library to strike up conversations with students about three of his favorite subjects: labor law, constitutional law, and politics.

“He was happy to discuss doctrine but happiest exploring the philosophical underpinnings of the rules as well as the impact various institutional decision makers had on the development of the law,” wrote former student Nell Jessup Newton ’76—who would go on to become a dean and professor at both UC Law SF and Notre Dame Law School—about Grodin for the Journal of the California Supreme Court Historical Society.

Whether discussing with students the legal aspects of Watergate, politely grilling a future colleague about the finer points of labor law, or writing a book about his brief but influential time on the California Supreme Court, Grodin made a lasting impression. Friends and colleagues have described him as a Renaissance man: an intellectual engaged in politics, culture, art, and law, at the same time unpretentious, modest, curious, and brilliant.

Grodin said he wanted to be a teacher from the moment he graduated Yale Law School and was grateful throughout his nearly 65-year teaching career to have worked alongside collegial, creative teachers and with the eager students in front of them in the classroom.

“Teaching for me has been a learning experience,” Grodin said. “If my students have learned from me half as much as I have learned from them, I will count my teaching as a success.”

Grodin joined the UC Law SF faculty full time in 1972, at a time when he said the law school was “changing in the direction of greater diversity among faculty and students, a greater emphasis on clinical programs, and a broader recognition of the relationship of law to social justice.”

During his years on the faculty, he helped promote the Workers’ Rights Clinic, which became the model for a statewide network of clinics assisting low-wage workers. He helped establish UC Law SF as a school where a student could get a strong education in labor and employment law, said Professor Reuel Schiller, who teaches labor law, administrative law, and legal history at the college. And he helped UC Law SF become one of the first law schools to modernize its curriculum by requiring all first-year students to take a course introducing concepts of statutory interpretation and administrative law.

During his years on the faculty, he helped promote the Workers’ Rights Clinic, which became the model for a statewide network of clinics assisting low-wage workers. He helped establish UC Law SF as a school where a student could get a strong education in labor and employment law, said Professor Reuel Schiller, who teaches labor law, administrative law, and legal history at the college. And he helped UC Law SF become one of the first law schools to modernize its curriculum by requiring all first-year students to take a course introducing concepts of statutory interpretation and administrative law.

“Joe believed it was imperative that students be exposed to the way contemporary government made public policy from the very beginning of law school,” Schiller said. “He wanted to ensure that the students had a practical language and framework for how to practice law.”

Schiller also recalled Grodin’s talent for putting people at ease while asking them difficult and probing questions. When Schiller interviewed for his job at UC Law SF in the mid-1990s, he gave a presentation to the faculty on labor law and history, well aware that the one person he would have to impress was Grodin. So when Grodin’s hand shot up with a question, Schiller was uneasy. Yet somehow, Schiller said, Grodin managed to ask a very insightful and technical question in a way that calmed Schiller’s nerves, allowing him to provide a suitable answer.

Leo Martinez, Dean Emeritus & Abramson Professor of Law Emeritus, remembered the exchange a bit differently, recalling that he might have been daunted by Grodin’s question: “I was thinking, wow, my ears would have been pinned back. My future colleague handled it well. In the end, he had no bigger supporter than Joe.”

Martinez, who taught a split section of contracts law with Grodin, described Grodin’s classroom style as laid back, which made students feel comfortable. At the same time, his superior intellect raised the level of discourse. “He’s just razor sharp in his use of the Socratic method,” Martinez said. “He homes in on the issue. He does it in a polite and understated—but very effective—way. He really enriched me as a scholar and a teacher.”

Early Life

To better understand Grodin, watch this 2015 documentary by Abby Ginzberg ’75, an independent documentary filmmaker, in which he describes experiencing anti-Semitism as one of the few Jewish students growing up in Piedmont, near Oakland.

“I came to understand what it was like to be an outsider,” he said. A trip to the Boy Scout Jamboree took him through the South, where he saw segregation and racism that further developed his sensitivity to people who were discriminated against.

After getting his bachelor’s degree from UC Berkeley, Grodin took the advice of labor lawyer Mathew Tobriner—a family friend who became his mentor—and went to law school, taking a job at Tobriner’s San Francisco law firm upon graduation and establishing himself as a go-to labor lawyer in his own right.

Labor Law and Public Service

Grodin served on the California Agricultural Labor Relations Board when it was created in 1975 to help farm workers unionize and bargain with California growers. He was described as the intellectual leader of the board, which was the first of its kind in the country and tasked with resolving high-profile conflicts between growers and workers.

In 1979, Gov. Jerry Brown appointed Grodin to the Court of Appeal, where he authored a landmark decision affecting worker’s rights. Pugh v. See’s Candy (1981) 116 Cal.App.3d 311, established that a contract of employment may contain an implied-in-fact promise that the employee would be terminated only for good cause.

Brown tapped Grodin for the California Supreme Court in 1982. Writing about his jurisprudence for the Supreme Court Historical Society in 2015, now-retired Justice Kathryn M. Werdegar said Grodin “exercised his judgment in a creative but disciplined and principled way, leaving a rich legacy of significant decisions that touch the lives of every Californian and continue to guide courts as they confront the issues of the day.”

Grodin’s time on the high court was cut short in 1986, when Grodin and two of his colleagues on the court, Chief Justice Rose Bird and Justice Cruz Reynoso, lost their bids to be retained by voters after a statewide campaign portrayed them as soft on crime.

The high court’s loss was UC Law SF’ gain. The faculty immediately voted to ask him to rejoin, said Dean Emerita and Professor Mary Kay Kane. “That is a testament to the high regard his colleagues had for him,” she said, “as sometimes when people leave and then want to return, they find that there no longer is a place for them.” It was a very long and successful marriage; he retired from full-time teaching in 2005.

Scholarly Impact

Professor Richard Boswell, Joe Grodin, Professor Karen Musalo

As a scholar, Grodin became an advocate for a novel idea of how courts should approach their work. He argued that when a constitutional issue is at stake, the courts should look first to the state constitution. Only if the rights at issue are not protected by the state constitution should a court look to the federal Constitution.

The California Supreme Court used that rationale—relying on the California Constitution’s right to privacy—when it upheld the state’s same-sex marriage law in 2008.

“Joe Grodin’s persuasive exhortation to judges and lawyers that they accord consistent and due recognition to independent state constitutional grounds in the development of the law continues to serve as one of his most significant contributions to the American system of justice,” former Chief Justice Ronald M. George wrote for the Journal of the California Supreme Court Historical Society.

“Joe is an amazing combination,” Schiller said. “He’s a genuine intellectual who has had life experiences that are deeply rooted in the practical and pragmatic world of how the government works. Bringing that combination into the classroom, as far as I’m concerned, that’s what makes law school great.”